Polymers are large molecules, composed of many repeated subunits. Due to their broad range of compositions and hence their different properties, many types of polymers - both natural and synthetic - play important and ubiquitous roles in everyday life.

The phase transition drives a switch

A special class are so called responsive polymers. These strongly change their properties upon a stimulus, like a small shift in temperature, pressure, pH value or salt concentration. This can be exploited in a number of applications. For instance, gels made from thermoresponsive polymers expand or contract significantly upon a small change of temperature. Therefore, they may serve as switches that open or close valves upon heating or cooling, for example in microfluidic chips. Such gels may also take up, transport and release substances like drugs and are therefore of interest as drug carriers. However, up to now, neither the pathway of the switching process nor the molecular origin of the behavior are well understood.

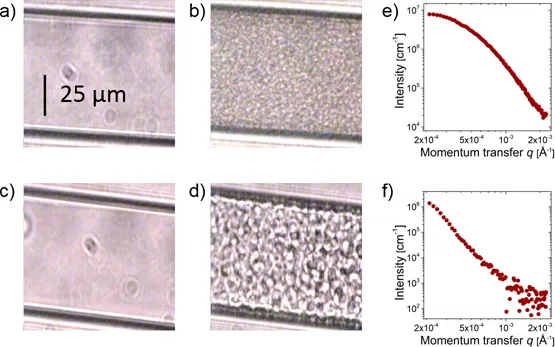

A solution of the thermoresponsive polymer poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) in water serves as a model system to study these effects. When such a solution is heated above the temperature of the phase boundary the polymers suddenly collapse, release water and form aggregates. However, at ambient pressure the aggregates stop growing at a size of about 100 nm (1/10000 mm or about 1/1000th of the thickness of a hair), and the expected macroscopic phase separation is never completed.

High pressure sheds new light on physics behind the phase transition

In order to learn more about this phase transition, a novel approach was required. The international team of scientists around Christine M. Papadakis, professor for soft matter physics at TU Munich, employed a shift in pressure to investigate the transition in more detail, combining the strengths of different experimental techniques like Raman scattering and small angle neutron scattering. This has two distinct advantages to the conventional approach on just probing different temperatures: Changing the pressure affects the hydration behavior and thus the solubility of the polymers, and pressure can be changed very rapidly across the solution, facilitating the characterization of the early stages of aggregate formation.

In order to test the hypothesis, that pressure has an influence on the formation of aggregates, pressures of a few hundred bars were employed. "Combining small angle neutron scattering experiments at TUM with Raman spectroscopy, we were able to show, that pressure indeed weakens the dehydration process of the phase transition. This leads to the aggregates formed at high pressures being significantly larger and having a higher water content", explains Professor Alfons Schulte, visiting professor from the University of Central Florida, USA.

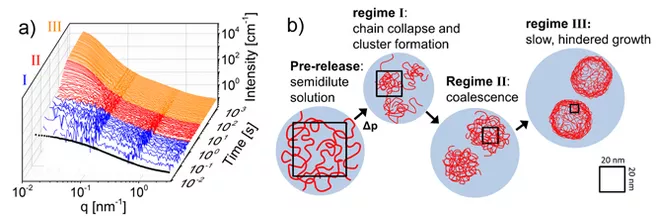

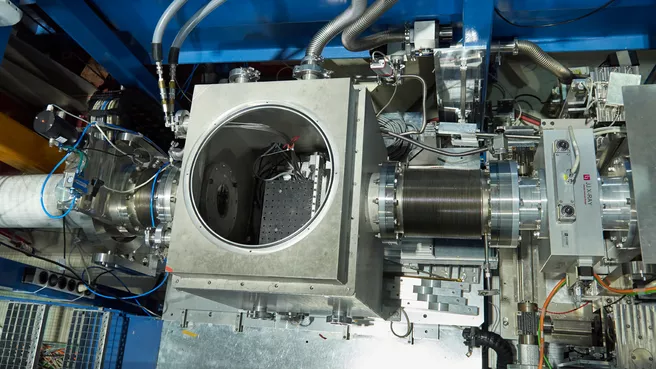

A further set of neutron scattering experiments were carried out at the Institute Laue-Langevin (ILL) in Grenoble. The temporal resolution of these experiments allowed the researchers to discern three different phases of cluster growth: Within the first second after the pressure jump, nucleation of the clusters takes place, followed by diffusion limited growth. After about 20 s, however, the growth of the globules slows strongly, as a dense shell emerges that hampers the merging of the aggregates.

Combining different experimental methods is the key

Christine Papadakis concludes: "Applying high pressure alters the hydration of responsive polymers, which has a strong effect on the structure in the phase-separated state. Our combination of different experimental methods has given us a comprehensive view of the structure-forming processes. A unique aspect is that time scales ranging from tens of milliseconds to thousands of seconds as well as length scales of around 1 to 100 nm are recorded. Our method creates new opportunities to study the pathways of structural changes in complex systems with unprecedented dynamic range."

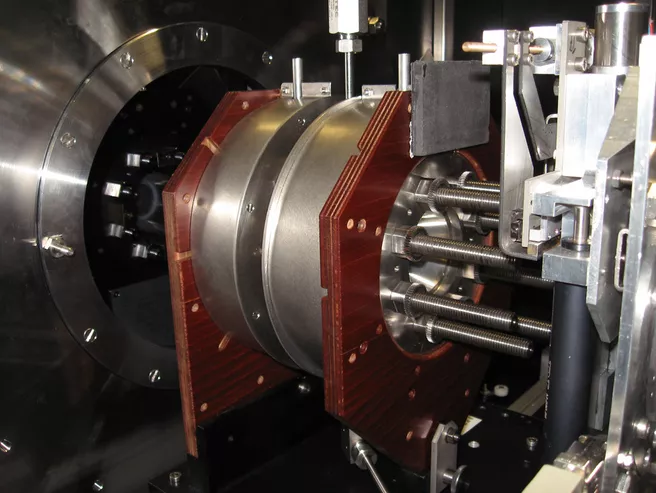

The work was carried out in a close collaboration of the Papadakis group with Prof. Alfons Schulte (University of Central Florida, Orlando, U.S.A.). Mutual research stays were supported by the TUM August-Wilhelm Scheer Guest Professor Program and the Faculty Graduate Center Physics of the TUM Physics Department. Neutron experiments essential for this research were conducted at the Heinz Maier-Leibnitz Zentrum (Garching) and at the Institute Laue-Langevin (Grenoble, France). The SANS High Pressure cell at MLZ is based on the one existing at the Paul Scherrer Institute (Villigen, Switzerland) (see reference in ACS Macro Lett. 6, 1180-1185 (2017)).

Text: Dr. Johannes Wiedersich / TUM

Original publications:

Pressure-dependence of Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) Mesoglobule Formation in Aqueous Solution B. J. Niebuur, K.-L. Claude, S. Pinzek, C. Cariker, K. N. Raftopoulos, V. Pipich, M.-S. Appavou, A. Schulte, C. M. Papadakis ACS Macro Lett. 6, 1180-1185 (2017) DOI: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.7b00563

Formation and Growth of Mesoglobules in Aqueous Poly(N‑isopropylacrylamide) Solutions Revealed with Kinetic Small-Angle Neutron Scattering and Fast Pressure Jumps B.-J. Niebuur, L. Chiappisi, X. Zhang, F. Jung, A. Schulte, C. M. Papadakis ACS Macro Lett. 7, 1155-1160 (2018). DOI: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.8b00605

More information:

News report at the University of Central Florida, USA

News report of the Institut Laue-Langevin, France

Contact:

Prof. Christine Papadakis

Fachgebiet Physik weicher Materie,

Physik-Department, Technische Universität München,

James-Franck-Str. 1,

85747 Garching, Germany

Tel.: (+49) 89 289 12 447,

Fax: (+49) 89 289 12 473

E-Mail: papadakis(at)tum.de

Prof. Alfons Schulte

University of Central Florida

Department of Physics and College of Optics and Photonics

4111 Libra Drive, Orlando, FL 32816-2385, U.S.A.

E-mail: Alfons.Schulte(at)ucf.edu